Eye Candy · 18 November 05

In an earlier entry I mentioned all of the gauges Eve has and how it would be nice to re-purpose a few of these for EV functions. There’s a gas gauge, engine temp, and engine oil that are no longer needed, not to mention a half dozen “idiot” lights.

Yesterday I pulled the instrument cluster apart and investigated the usability of the meters. The bad news is that I probably can’t use them.

The good news is I got some great pictures!

First off I should admit that today’s entry is mostly a shameless excuse to show off a bunch of photos. I was taking a few pics using the lighting box and noticed that they were pretty cool looking, so I just kept on snapping.

And rather than make little thumbnails, I decided to embed full sized images in the article. Actually, the first image IS a thumbnail, click it for a much larger version. My favorite.

Sorry to those of you on dial-up.

Still, I’ll try to intersperse technical info with the eye candy.

For those unfamiliar with these types of meters here is how they work.

The U-turn looking piece of metal with white wire wrapped around it is bi-metal. Bi-metal is used to change heat energy into mechanical energy. One way to think of the metal is that it has two shapes: a cold shape and a hot shape.

In the case of these meters the “cold shape” is mostly straight. When you turn on the car it applies a voltage to one side of the white wire, while the other end is hooked to a variable resistor. For example, the engine temperature meter is connected to a sensor embedded in the engine block that becomes lower in resistance as the engine heats up.

As resistance goes down more current flows through the white wire. The white wire has it’s own resistance which is turned into heat as current flows through. This warms up the bi-metal, which starts bending towards its “hot shape,” dragging the meter pointer along with it.

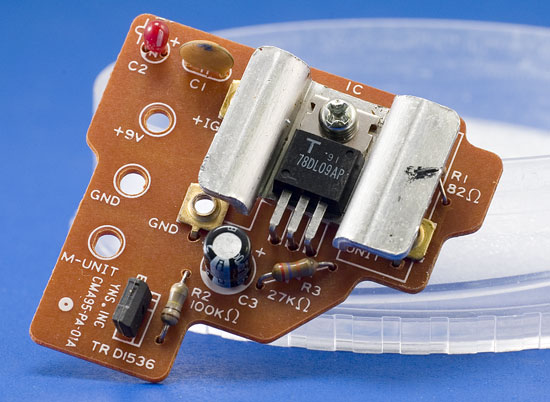

The engine heat gauge has it’s own 9 volt regulator, pictured here. The other meters use a 7 volt regulator that I’ve haven’t uncovered yet.

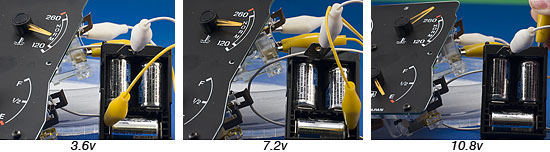

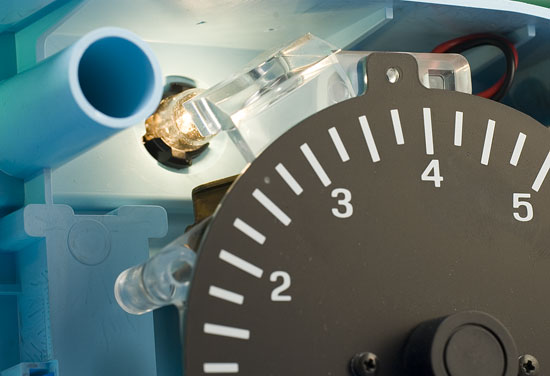

In this series of photos I’ve connected three different voltages to simulate the car. A better method would be to supply a steady 9volts and vary a series resistor, but this is close enough.

The batteries are 3.6 volts each and in each picture I add another battery. You can see that the final, 10.8 volt connection pegs the meter.

As voltage is changed the response isn’t instantaneous. Instead the meter slowly creeps up (or down).

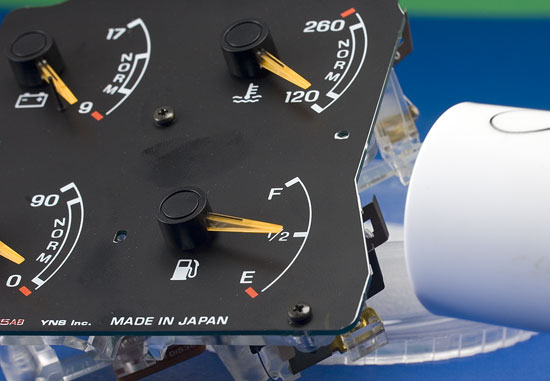

Hey, you don’t even need electricity. Here you can see that I’m “filling the gas tank” simply by blowing a hair dryer on the fuel gauge.

If only!

This illustrates one of the shortfalls of this type of meter: temperature sensitive. A half full tank of gas will probably register a different reading on a sub-zero day vs. a 100+ day. I suspect the engineers assume you’ll run the heat or air conditioning to moderate the passenger compartment temperature.

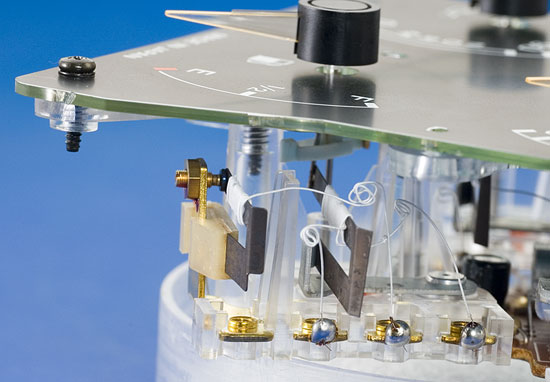

Here’s a side-view of the fuel meter mechanics. Note that there’s an extra bi-metal strip. This extra strip opens and closes a contact, much like a home thermostat. In this case I think it is used to indicate when the fuel is empty, interrupting power to the meter since it’s probably not all that accurate and might show “a little bit” of gas left.

Which is why these meters aren’t very useful for what I had in mind. I thought it would be nice to use one of them to show the pack voltage and another to show the current. But the meters, actually the bi-metal, is too slow in responding to changes and aren’t all that accurate.

The back view of the four meters with 9v regulator in place. The bottom right, silver meter is for battery voltage. I didn’t open it up but I suspect that it doesn’t use bi-metal in order to provide faster results and improved accuracy.

Note all of the clear plastic on the back side of these meters. That is a light channel. One or two bulbs shine into the edge of the plastic, which in turn lights all of the plastic. The meter faces have openings which let the light out.

Here’s a better view of the light channel lined up with its light bulb. For this meter there’s another bulb at a bottom light channel.

These bulbs are controlled by the dash lighting control, which varies the voltage and thus changes the brightness.

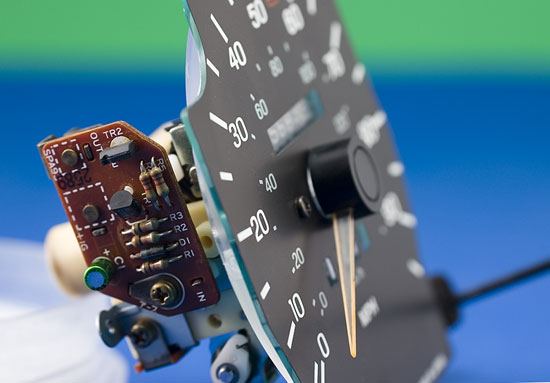

Here’s how one of the meters look with backlighting on. You can see how the mph numbers let light “ooze” through, while the odometer is merely lit up by the plastic light channel surrounding it.

I think one reason for this approach is to cut down on the number of light bulbs needed. It also provides a better, more consistent blend of light.

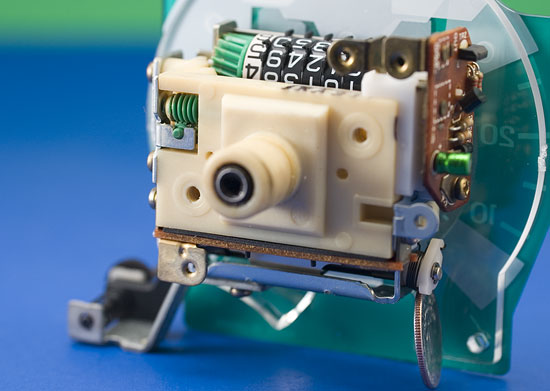

This is the speedometer. The center port is where the mechanical speed cable from the transmission connects. Inside and behind the plastic are a series of gears to translate rotations into ticks on the odometer and move the mph gauge.

Not really shown is the mechanical linkage for the trip meter control. When pushed in and turned it is connected to another gear that allows the trip odometer to be reset.

Side view of the speedometer. The circuit board is a speed sensor. They don’t really go into it much in the manual, but I suspect that it is used by the onboard “courtesy lighting and buzzer-from-hell” computer to know when the car is moving in order to trigger the seat belt lighting warnings.

At least it’s not a talking car…

“You appear to be moving. Wouldn’t you feel more comfortable in the warm embrace of safety restraints?”

“I would certainly feel much better if you were restrained. Of course I only have your interests in mind.”

“Hello? Dave? What are you doing Dave…”

The pictures are very good. But the coolest thing i found while looking thru them is that the mileage on your odometer is almost identical to that our my own vehicle as i drove it to work today. (not a Probe). Thanks for the great site. I look forward to the updates. Frank

Great breakdown analysis! Good use of a quarter, too. ;-)

Can it sing “Daisey?”

Thanks, Franks!

Ted: money is a cheap prop.

Dan: well, it IS losing its mind.

I replaced heater core in my Nissan 240SX this week. Knew there was trouble when the first instruction was to remove the front seats. Nothing left but steering wheel and wiring harnesses. Did you mount your e-heater where your old one was? Do you worry about melting the housing if the heater door would shut etc? I’ll send you a picture of my installation. My instrument cluster appears to be all one circuit board. No mechanical cable for spdmtr even. I hope I can put it all back together.

Hi Woody,

Oh, man, sorry to hear that, hope it goes back together fine.

Would love to see pics, I’ll send an email.

If memory serves correct there was one door which could be closed. I disconnected the dash control from it and wired it permanently open.

Again, thanks, Jerry. Mine is a 1980 Triumph Spitfire.

I took the liberty of printing out a couple of your photos of the speedo etc. to show a friend and he had a really relevant comment. “Why don’t the likes of Haynes and Chilton (the workshop manual folks) use photos of this quality in their workshop manuals. After all a picture speaks a thousand words and they could be less “wordy” in their attached descriptions if their photos were much clearer. Their manuals would probably end up less bulky and translations to other languages would be simplified as well.”

I think he has a great point

Cheers, Alvan Judson

Thanks Alvan, and thank your friend for the compliment.

Good idea. Hey, they could send the car or car parts to me and I’d take the pictures for a reasonable rate! ”:^)

Hi, I need a photo of SPEED SENSOR,for FORD PROBE 1994. Could someone send it to me, please? my e-mail Dj.and1@one.lt or pakapenai@yahoo.com . thanks

Is that why my 89’s gas gauge never worked quite right? Hmmm…

Ugh, that gas gauge is horrible! I see now why cars went to resistive sensors in the gas tanks (And then to computer-monitored resistive sensors with smoothed output)